In March of 2014, I went on a “March Madness” tour to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. I went on the same tour as Jan van der Aa and his sister, which was nice.

I had to travel through China, so I got a dual-entry visa and traveled to Peking. Although I wasn’t going to stay there for 72 hours, I couldn’t take advantage of the visa-free entry, because the Communist Party only let Norwegian citizens stay for 24 hours without a visa. I suspect they were angry about the Nobel Prize that went to Lau Hiubo (劉曉波). Thanks, Nobel Committee.

We had a briefing at Koryo Tours office, and left in a bus the next morning. I almost missed it, because I stupidly forgot my card in an ATM and ran back to retrieve it. Fortunately, the employees at Bank of China (中國銀行) were coöperative, so I got my card back and ran back to catch the bus.

When we got to the airport, we met our first north Koreans. They had just played in a football tournament, but were beaten by Portugal. It was very interesting to hear them call each other “comrade” (同志 to superiors, 동무 to everyone else). It was also fun to try talking to them in rudimentary Korean.

One of my favourite moments was when we boarded the plane. Leaving the generic-looking Chinese airport and being plunged into the atmosphere of the Air Koryo plane (from the Soviet era) was quite an experience. One of my favourite songs, My Country is the Best (내 사는 내 나라 第一로 좋아), was playing (and yes, they kept playing music until we landed). The stewardesses (all of them were female) were beautiful, and I got a seat right next to one of them. I didn’t get to take a picture with her, but since we got a newspaper that had Kim Jong-un on the front page (which every newspaper does), she did show me how to fold it in a respectful way. You can’t fold the leader of the country, so you have to fold the top and the bottom of the paper instead of the middle. The meal on the plane was something that looked like a hamburger. It was OK, I guess.

When we landed, we were reminded not to take pictures of any unfinished structures (finishing building projects quickly is apparently a matter of national pride), the military, or anything else that might put the country in a bad light. Other than that, we could take as many pictures as we liked.

We met a pair of guides, and when one of them said her name was Hwang (黃), she did it with a rising tone, so without thinking, I asked if she was Chinese. That was embarrassing. Fortunately, our guides turned out to be another pair, and they were great guides, too. Very friendly and good at their job. Both of them were called Kim (金).

On our way to Ryanggang Hotel (兩江호텔), we stopped at Pyongyang’s Arc of Triumph (凱旋門) and saw some kids on roller skates. While driving through Pyongyang, we could see the unfinished Ryugyong Hotel (柳京호텔) in the distance. Its exterior is finished, so we were allowed to take pictures of it.

We also passed the Chollima Statue (千里馬銅像), but never ended up visiting it.

The hotel was beautiful, and there was a bookstore in the lobby. By the end of the trip, I bought a book that was all about what a great man General Kim Jong-il was.

The room was one of the best I’ve ever stayed in, but I don’t usually stay in hotels anyway. It was very clean, and the bed was comfortable. The electricity kept going off, but that was convenient, because I couldn’t figure out how to turn off the lights. The downside was that I woke up every time the power came back. I found out how to control the lights eventually, and had a great night’s sleep.

Day 1

We had breakfast downstairs, and it included some great pancake things that I haven’t been able to find since. The waitress called them 알라지 (I had her check my spelling, too). The tea was also fantastic. I don’t think I’ve ever had tea that good.

As we drove through Pyongyang, one of the things I really liked was the absence of advertisements. There was a lot of slogans and calls to support the Party, but the only ad was for Pyonghwa Motors (平和自動車).

The bus took us to Kumsusan Palace of the Sun (錦繡山太陽宮殿), where the bodies of President Kim Il-sung and General Kim Jong-il lie in state. This was the most solemn part of the tour, and I had to wear a suit. We had to pass through several wind machines that blew off dust and hair from our clothes, and we walked through long corridors filled with art and other things commemorating the two leaders. We couldn’t take pictures inside, and we had to keep our arms straight down at all times. I absentmindedly put my hands behind my back at one point, and the other group’s guide scolded both me and our guide for it. Oops.

We got to see both of the leaders, and participated in a bowing ritual in order to walk around the body. First, we faced the feet and bowed. Then, we faced the body’s left side and bowed. Then, we faced the head without bowing. Then, we faced the right side and bowed before moving on to the next room. We did a lot of bowing on this trip.

Afterwards, we took pictures outside before moving on to the Revolutionary Martyrs’ Cemetary (大城山革命烈士陵), where, among others, Kim Jong-suk, President Kim Il-sung’s first wife, is buried.

Next, we visited the Mansudae Grand Monument (萬壽臺大紀念碑), where we bowed to the bronze statues of President Kim Il-sung and General Kim Jong-il. Any pictures of the statues had to include their whole body, not just part of it.

We could also see the Grand People’s Study House (人民大學習堂) on the way.

Finally got a passable picture of the Ryugyong Hotel!

These signs were everywhere, with varying messages and slogans on them. This one says 「先軍朝鮮의 太陽 金正恩將軍 萬歲!」 (“Long live the sun of Songun [‘military-first’] Korea”) in Korean letters, since Chinese characters are even rarer in the north than in the south.

Then, we visited President Kim Il-sung’s childhood home, where we saw this strange pot, which I’m sure I’ve seen on the Internet before.

Day 2

On the third day, we went to Kim Il-sung Square (金日成廣場), where the famous military parades are held.

There was no parade when we were there, and they are actually quite rare, but we did see the markings that make them possible.

This is the other side of the Grand People’s Study House, where the leader overlooks parades.

On the other side of the Taedong River (大同江), we could see the Juche Tower (主體思想塔).

We walked down the street to the foreign bookstore (外國文冊房). Our British tour leader set up the tour so that we could walk among normal people. We could also talk to them, though we didn’t have that much time.

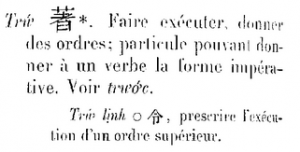

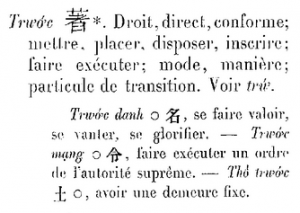

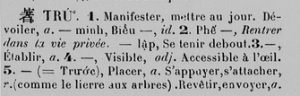

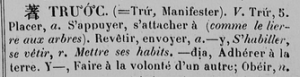

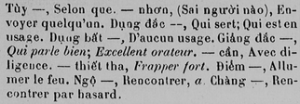

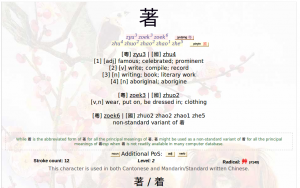

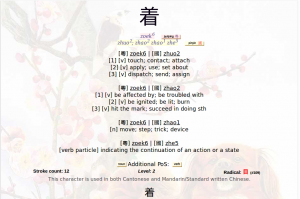

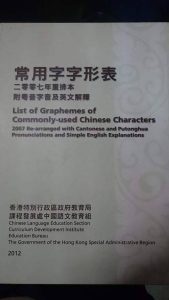

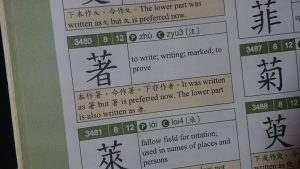

Before going, I was told that, although we could pay in USD, RMB, or EUR, the best deals were in dollars. That was not the case. The fixed rate made EUR the best choice nearly 100% of the time, so I ended up borrowing Euros from Jan and pay him back in dollars later, using the actual rate. In this case, I bought a dictionary.

Afterwards, we went to the Pyongyang bowling hall. It was fun, and even though the power went out a few times, the machine still kept track of our scores.

Then, we drove to Kaesong (開城), where we stayed in a historical guesthouse. I opted not to shower there, since everything was old-fashioned, the water was cold, and I was lazy.

The food was great as usual.

There was also a dog soup option, which the Koreans call “sweet meat soup” (단고기국). The taste was OK, but I couldn’t finish it.

Day 3

From Kaesong, the Demilitarized Zone between north and south Korea was close by. We went to the Joint Security Area (共同警備區域) and the Peace Museum (朝鮮民主主義人民共和國平和博物館).

We even got to see some tourists on the south Korean side. We waved at them, but they were not allowed to make any moves back. It’s more relaxed on the northern side.

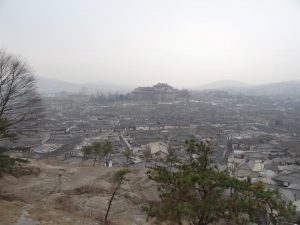

After that, we went back to Kaesong and up on a hill that overlooks this historical city.

We made sure to bow to this statue of President Kim Il-sung, of course.

We had some great food once again.

Then, we went to a museum. Apparently, it’s famous for its ginseng.

On the way back to Pyongyang, we stopped at this monument, the Arch of Reunification, or Monument to the Three-Point Charter for National Reunification (祖國統一三大憲章記念塔).

Then, we went to visit the Juche Tower. Too bad it was on the only cloudy day. The guides told us about the symbolism behind its measurements, and how it was completed ahead of schedule.

There were plaques for all the major donors to the tower.

I went to a public toilet, and took this picture on the way. The toilet was very clean, but I don’t have a picture of it.

It was too cloudy to get a good picture from the top, but there’s Kim Il-sung Square.

Next stop was the Monument to Party Founding (黨創建紀念塔). It was pretty cool, and the local guide was very friendly. I asked her how to say “the Workers’ Party of Korea” (朝鮮勞動黨) in Korean, because I wanted to hear whether she would say 「로동」 or 「노동」. She and another guide said 「조선노동당」 at the same time. Since I didn’t want the preceding /n/ to interfere, I repeated 「朝鮮…?」 to get them to say the next part. The man said 「로동당」, but the woman said 「노동당」, even though they were both from Pyongyang. Interesting.

Here’s Mansudae in the background. Lights go on at night to make sure the leaders’ faces are always lit up. Most of them stay on even when the power fails.

We went to visit an art gallery with lots of beautiful paintings. Many of them were of nature, but there were also quite a lot of revolutionary motifs. Mt. Paektu, the Arirang Mass Games, and a painting of the Young Pioneers that looks like an actual photograph! I also liked the painting of all the major monuments of Pyongyang.

And, of course, the President and the General.

Afterwards, we went to a brewery. I don’t drink, so it wasn’t that interesting, but the waitresses were cute.

On the way back to the hotel, I noticed that the Juche Tower actually lights up at night. Cool, but I couldn’t get a good picture of it.

Day 4

On the fourth day, we first went to Pyongyang Railway Museum (鐵道省革命史蹟館). It was mostly about the train travels of the President and General.

Most interesting to me were the old newspaper articles in mixed script. I took so many pictures of newspapers that I ended up lagging behind the group.

As always, there was a lot of information about President Kim Il-sung and General Kim Jong-il too. Not all of it had to do with trains, either.

They had a lot of old trains.

Next, we went to take the Pyongyang Metro (平壤地下鐵道). The escalator went deep down into the ground.

The metro has two or three lines; the Chollima Line (千里馬線) and the Hyoksin Line (革新線), and then there’s the Mangyongdae Line (萬景臺線), which seems to be an extension of the Chollima Line. You can press a button to activate lights that show you where to get on and off.

The stations on the Mangyongdae Line are very impressive. We started at Puhung Station (復興驛).

Then, we took the metro to Yonggwang Station (榮光驛). I was happy to hear another song I like, It is War (攻擊戰이다).

Finally, we took the metro all the way to Kaeson Station (凱旋驛), which is where the Arc of Triumph is. On the way, I sat next to a young girl who was studying Mandarin. Her English was good, too.

At Kaeson Station, this message says 「온 社會를 金日成-金正日主義化하자!」 (“Let’s Kimilsungism-Kimjongilism-ify the whole society!”) in Korean letters.

We got peach ice cream, or “eskimo” (에스키모) as the Koreans call it. It was good.

Next, we went to a factory museum. It had this interesting message: 「石炭은 工業의 食糧이다」 (“Coal is the food of industry”).

There were many old machines there.

Then, we passed one of the few things in Pyongyang to survive the Korean War, or Fatherland Liberation War (祖國解放戰爭), as they call it.

Next stop was the Grand People’s Study House, which we got to enter this time. Apparently, any citizen of the DPRK can use a computer with an Internet connection to order books from this grand library. I tried searching, but the Korean keyboard wasn’t indicated visually, and it wasn’t a layout I was familiar with.

Here’s the view of Kim Il-sung Square from the balcony, with the Juche Tower in the background.

Next, we went to my favourite museum: the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum (祖國解放戰爭勝利紀念館).

They had lots of cannons, tanks, submarines, and planes.

I love the northern spelling of “tank” (땅크).

We also visited the captured American ship USS Pueblo.

And we watched this fantastic video. It puts a smile on my face every time.

Then, we entered the main museum. Unfortunately, we weren’t allowed to take pictures inside, but it was a great experience. There was a life-sized model of President Kim Il-sung greeting us in the lobby, and the building looked kind of like a luxury hotel.

I also saw these around the city. They say 「偉大한 金日成同志와 金正日同志는 永遠히 우리와 함께 계신다」 (“The great Comrade Kim Il-sung and Comrade Kim Jong-il are with us forever”) in Korean letters.

After the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, we drove through the countryside again.

On the way to Pyongsong, we could also see slogans in the countryside. This one says 「榮光스러운 朝鮮勞動黨 萬歲!」 (“Long live the glorious Workers’ Party of Korea!”) in Korean letters.

The hotel in Pyongsong was much smaller than the one in Pyongyang, but very cozy. The staff was super friendly. I was tired, so I went to bed early and missed the karaoke. Bummer, since I love north Korean music and would have loved to join.

Day 5

The next day, we went to a camp that served as a base of operation against the Japanese (or Americans … I forgot which).

On the way back to Pyongyang, we stopped at a candy factory. I bought four bottles of soda, because they were only 5 RMB each. The strawberry one was the best, but the peach one was OK too. The other two weren’t that good.

We also visited Kim Jong-suk Middle School No. 1 (金正淑 第一 中學校). I sang Chollima on the Wing (千里馬 달린다) and No Motherland Without You (當身이 없으면 祖國도 없다) with one of the classes.

There was a strange taxidermy room. The animals were kind of weird.

We left Pyongsong and headed to a “village” of movie backgrounds. There were areas for ancient Asia, South Korea, China, and more.

It was cool to walk through.

I saw only one church building on the trip. Apparently, it is in use.

Then, we went to another art gallery. I talked to a multilingual woman who knew French, among other languages.

After that, we went to visit the famous Yanggakdo International Hotel (羊角島國際호텔).

We had to visit the top floor with the revolving restaurant, of course.

After that, it was time to take the train back to China.

Got a few good pictures of the Korean countryside.

Finally, we reached Tantung (丹東). It was an interesting feeling. I felt safe in the DPRK, but not very free, since we had to stay with the guides at all times.

The train we travelled with didn’t have any toilet paper, but I had brought my own just in case.

One of the guards also had this strange mix of simplified and normal characters on his shoulder. All the other ones had it all in simplified.

I enjoyed the train ride, although it was about 24 hours long from Pyongyang to Peking.

I skipped a couple of things, like the grave of an ancient king near Kaesong and the store selling lots of imported goods, but I didn’t get any good pictures there. I hope I can visit some other places if I come back in the future!