Few characters are as quirky as 著. It seems to have been a variant that eventually split off from 箸, and now its own variant 着 is in the process of splitting off from 著. This illustrates a trend in the development of Chinese characters: they often start out as one sign that may represent several different (though usually similar-sounding) syllables and thus several meanings. Then, they split into more signs that share the burden of sounds and meanings associated with them. It’s rare for characters to merge, but there are many examples of such splits.

The Republic of China

It has been assigned 5 common readings in the national language of the Republic of China, or Standard Mandarin: ㄓㄨˋ、ㄓㄨㄛˊ、ㄓㄠˊ、ㄓㄠˉ、˙ㄓㄜ (zhù, zhuó, zháu, zhāu, zhe), as well as 2 that are rare enough to be ignored: ㄔㄨˊ、ㄓㄨˇ (chú, zhǔ). As far as the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China is concerned, 着 is a variant of 著, and that’s the whole story.

ㄓㄨㄛˊ is a merger of two Middle Chinese readings: one with a voiceless initial consonant, and one with a voiced one (cf. Cantonese zhoek³ and zhoek⁶). It is interesting to note that ㄓㄨㄛˊ and ㄓㄠˊ probably both developed from the reading with the voiced initial (one being literary and the other colloquial), but they ended up acquiring different meanings. ㄓㄠˉ is possibly a further development of the latter.

˙ㄓㄜ is a Mandarin-specific particle that had to be written down somehow, and this character did the job.

ㄔㄨˊ is only used in 著雍・著雝 (ㄔㄨˊ ㄩㄥˉ [chúyūng]), an alternate name for 戊, the fifth of the ten heavenly stems (十天干). ㄓㄨˇ is only used in 著任 (ㄓㄨˇ ㄖㄣˋ [zhǔrèn]), but I’m not sure what it means. Most dictionaries ignore these two, for obvious reasons.

Japan

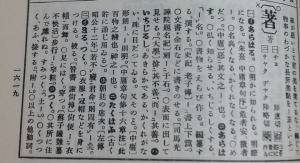

In pre-war Japan, the situation was the same: 著 had two Sino-Japanese readings (since Japan never had the ㄓㄨㄛˊ–ㄓㄠˊ–ㄓㄠˉ split or a reading corresponding to the Mandarin particle): チョ and チャク (cho and chaku). Here from 詳解漢和字典, published just after WWII, identifying 着 as a vulgar variant of 著.

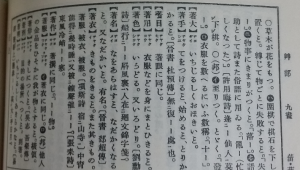

And here is the 著 entry in the same dictionary:

However, after WWII, 著 and 着 were assigned different roles: 著 for チョ, 着 for チャク. Native Japanese readings follow the meanings connected to the Sino-Japanese readings, so 著 for あらはꜜす and いちじるしꜜい (arawaꜜsu and ichijirushiꜜi) and 着 for きる and つꜜく・つくꜜ (kiru and tsuꜜku/tsukuꜜ).

Mainland China

When the Communist Party of China developed their standard, they assigned the two characters the same roles as the Japanese. 著 for ㄓㄨˋ, 着 for ㄓㄨㄛˊ、ㄓㄠˊ、˙ㄓㄜ and ㄓㄠˉ (this last one is also written 招, since they sound the same in Mandarin).

Korea

Korean usage is the same as well, suggesting this usage wasn’t just invented after the war. Korea never had any major character reforms, and still 著 is usually reserved for 저 (chŏː) and 着 is usually reserved for 착 (ch’ak). However, either can be used for either reading. In practice, though, most Koreans unfortunately don’t use characters at all anymore.

Vietnam

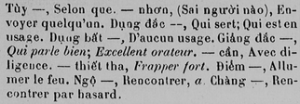

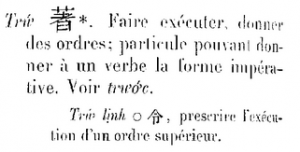

In Vietnam, characters are unfortunately used even less than in Korea, but dictionaries from the late 1800s suggest trứ and trước were both written 著, as in the Republic of China. Interestingly, there doesn’t seem to be a trược reading (corresponding to a Middle Chinese voiced initial consonant) for this character. The meanings that would be associated with that reading are listed under trước.

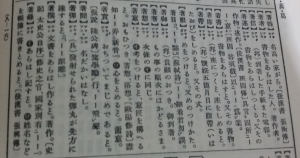

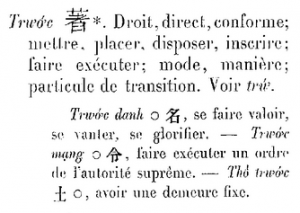

著 (trứ) in Bonet’s (1899) Vietnamese–French dictionary:

And 著 (trước) in the same dictionary:

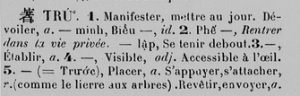

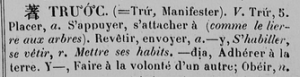

著 (trứ) in Génibrel’s (1898) Vietnamese–French dictionary:

And 著 (trước) in the same dictionary:

Modern dictionaries do include 着, and though they seem to prefer the reading trước for it, some also list trứ. 著 is always listed with both readings.

Hong Kong (and Macau)

Until recently, I was under the impression that Hong Kong usage, and presumably Macanese usage as well, differed from all of the above. CantoDict distinguishes them this way: 著 for zhy³ (ㄓㄨˋ) and zhoek³ (ㄓㄨㄛˊ), 着 for zhoek⁶ (ㄓㄨㄛˊ、ㄓㄠˊ、˙ㄓㄜ and ㄓㄠˉ).

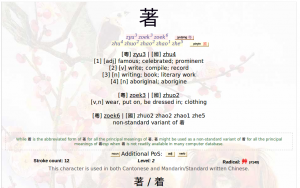

著 in CantoDict (24.04.2017)

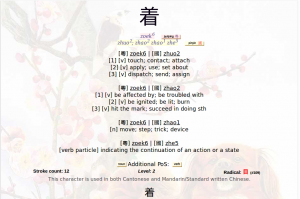

着 in CantoDict (24.04.2017)

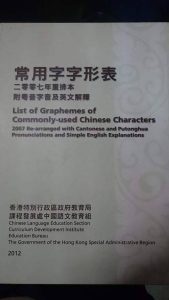

However, my friend Kumono Shōta showed me the List of Graphemes of Commonly-used Chinese Characters, published by the Hong Kong Education Bureau. I was surprised to learn that people on the CantoDict forums seem to be wrong about the official Hong Kong division of 著 and 着. According to this list, 著 is for zhy³ (ㄓㄨˋ) and 着 is for zhoek³ (ㄓㄨㄛˊ、ㄓㄠˊ、˙ㄓㄜ and ㄓㄠˉ), just like in all the other jurisdictions (except for the Republic of China, of course).

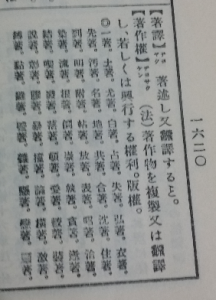

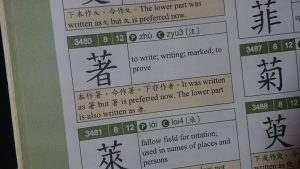

著 in the List of Graphemes of Commonly-used Chinese Characters:

着 in the List of Graphemes of Commonly-used Chinese Characters:

Correspondance List

I made a list with the readings and the meanings the characters (roughly) correspond to!

Mandarin – Cantonese – Japanese – Korean – Vietnamese – English

ㄓㄨˋ – zhy³ – チョ – 저 – trứ – notoriety, authorship

ㄓㄨㄛˊ – zhoek³ – チャク – 착 – trước – to don

ㄓㄨㄛˊ – zhoek⁶ – チャク – 착 – trước – to make contact, to apply

ㄓㄠˊ – zhoek⁶ – チャク – 착 – trước – to ignite, to affect

ㄓㄠˉ – zhoek⁶ – チャク – 착 – trước – (boardgame) move

˙ㄓㄜ – zhoek⁶ – チャク – 착 – trước – stative particle