I like learning languages, and I’ve liked it since I started learning French in middle school. However, the joy was always lessened by the time it took to learn enough vocabulary. I would start to learn, and I would always forget most of the words and have to cram them again. However, when I first heard (or read, rather) about David James in “The Polyglot Project” a year or two ago, he mentioned a certain “Goldlist Method” that was supposed to facilitate vocabulary learning. I was in Japan at the time, trying to learn characters with the Heisig method and flashcards, and cramming vocabulary for weekly tests, and I thought that maybe I had finally found the method to use. I searched for it, and that search led me to David’s site, where the method and the ideas behind it are explained in great detail in this post and these videos. I want to try to summarize the method and share some of my experiences with it.

What you need

First, you pick a language to goldlist. Any language works, in theory, but you will need to be a little creative if you’re dealing with a vertical writing system, and to a lesser degree languages written right-to-left. Also, while it would probably be possible to goldlist more than one language in the same book, I wouldn’t advise it. I like keeping separate lists of vocabulary, so that I know approximately how many words I know for each language.

When you’ve picked your language, you need a book for goldlisting it. A standard goldlisting book should have at least 35 lines, although it’s even better to have more space. The best books I’ve found have 35 lines and are 100 pages thick. Basically, the thicker, the better. If you want to learn 10 000 words, you will probably need several books anyway, so it’s better to have a few thick ones than many, many thin ones. For each thick book (which is often called “bronze book”), you’ll also need another one that is 1/4 the size, or four books to one (the smaller ones are called “silver books”). Also, you will obviously need something to write with. I like to use four different colours of pens, as you’ll see in the images below, but you don’t have to.

One of the most important things you need, is a source to get your words from. You can use a dictionary or the Internet, but I like to use the word lists in a textbook, because good textbooks have common words that you’ll need to know. If you don’t have a list of words ready, you can also make one yourself by collecting the words before goldlisting them. For most major languages, though, you probably won’t have to make your own list. There are several readily available if you search for them. I’ve found lists containing up to 10 000 words for Mandarin Chinese, and similarly for Japanese. These languages are very easy to make lists for, since you don’t really need to learn any grammar associated with each word, while for French you need to make sure the list includes e.g. the gender of nouns and so on. Because of this, I like to learn how the language works and what I need to know about each word before starting a giant goldlist.

Before you start goldlisting, you should be able to pronounce and read the language you are learning. For this, you can use a native friend or teacher, an audio course, or simply learn some basic phonetics and find a study of the phonology of the language you want to learn. No matter what you do, it’s always good to have a native speaker that you can ask if you need to, and it will always help your pronunciation to imitate them. They won’t necessarily be able to explain to you how to pronounce their language, though, which is why I prefer checking Wikipedia’s articles on the phonology of a language first.

How it works

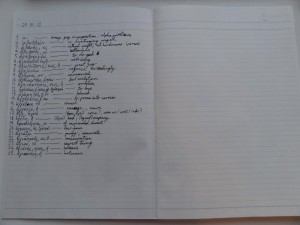

If you have everything you need, you can get started by opening your notebook on the very first double page. That’s important. Starting on the top left, number the lines from 1 to 25 and enter one word with a translation/short definition on each line. Don’t put too much on one line in the beginning, as you will remember (on average) 30% of what you write, and then remove 30% of the lines. If you have too much on one line, you may find that you remember only half of the line and it will be troublesome. Remember to note the date; that is very important!

Here is an example picture from my very first page of New Testament Greek. Notice that it’s numbered 1 trough 25; the next page has 26 through 50, the third has 51 through 75, the fourth has 76 through 100, and so on. That makes it easy to check at any time how far you’ve gotten, and it serves as motivation, especially if you have a goal you want to reach. As you can guess from noticing that all the entries start with alpha, my source is a dictionary.

When you have finished writing the 25 entries, you can read through the list aloud. Take a break for at least 10-15 minutes, doing something different to allow the long term memory to rest. The actual writing should take about 20 minutes at a relaxed pace. Make sure you’re enjoying the process to maximize learning; don’t do it when you’re too tired or otherwise unable to concentrate or have fun.

You’ll have finished the page for now, and can go on to page 2, or simply close the book. You can do as many pages as you want in one day, as long as you don’t do the same page more than once. You cannot look at the list again until at least two weeks have passed since the date you wrote on the page. This is very important, and the very foundation of the Goldlist Method. It is basically the only non-tweakable part of it. The reason is that you want to make sure the words are not stored in your short-term memory anymore, because only then will you be able to check what words are stored in your long-term memory and are ready to be removed. You can wait longer than two weeks if you want, but never less.

After the two weeks have passed, you may come back to the list and check which words you know best. You don’t need to test yourself by holding a hand over the translations, but just be honest with yourself and remove the words you know best. Removing them is the last step in remembering them anyway, so don’t worry too much about it. Since you are removing 30%, the closest is 8 entries. If you simply can’t remove that many, you can “cheat” by combining two lines into one. You can even turn them into sentences or phrases. I once did this to make a sentence that went something along the lines of “the little girl raped the bank account”.

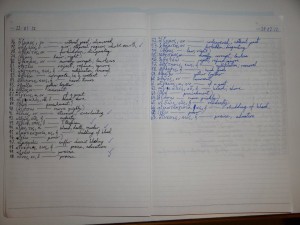

After removing those 8 entries, you put the remaining 70% into the top right page, numbered 1 through 17. Although this picture is a bit further in the book, you can see that the lists’ numbering follows their “twins” from the previous page. Don’t forget to write the date!

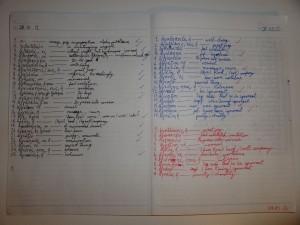

Now you simply repeat the process. You can add more pages, distill existing ones, but never look at a list before two weeks have passed. So, after two weeks, you come back and weed out the 30% you know, in this case that translates to 5 entries. Then you put the remaining 12 entries on the bottom right. And put the date, of course!

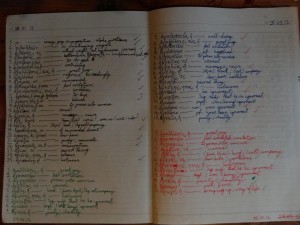

You can see that I’ve cheated and already put a 1 where the next list will be. After two weeks or more, you come back and weed out 30% of 12, which will be 3 or 4. Well, if you are confident that you know more, you can remove more. You can see that the second distillation in my picture actually has 10 instead of 12 for that precise reason. It doesn’t always happen, so you shouldn’t expect it, but when it does, you can just keep going with a shorter list. That goes for all distillations. Put the third distillation on the bottom left, and wait for another two weeks or more. I haven’t gotten this far yet in my Greek list, so I’ll use a picture from my Japanese silver book to illustrate instead.

This is what a book looks like when it’s completely mature. After two weeks, you come back and check what 30% you know, which should be 2-3 entries at this point. The further you get, though, the more likely you are to be able to eliminate more than 30%, and that is often the case here. If you can do that, then it’s good, but be honest with yourself.

At this point, you need to collect the words you don’t know from several pages until you have 25. Then you put those words into the silver book in exactly the same way that you originally put them into the bronze book, and you repeat the whole process in the new book. If you remembered 30% every time, then the silver book will contain 1/4 of the entries you put into the original headlist.

When you have fully distilled the silver book, you probably won’t have many words left. If you want to, you can keep putting them into new books for as long as you want, but it’s really not necessary. When I finished my Chinese silver book, I went through it and picked out all the words I knew least, and put those into a new book; a “gold book”, if you will. My original headlist was approximately 2000 entries, and the gold book contained only 50 words. If I did as many as 10 000, it would probably contain 250, which isn’t really worth its own book, but you can use the same gold book for several languages if you want to.

Why it’s awesome

The Goldlist Method optimizes learning to the long-term memory. In a way, it isn’t concerned with the short-term memory at all, except by making sure it doesn’t interfere. It is the most efficient system that I know of for learning to the long-term memory. It’s also fun, and I’d say addicting. On occasion, I’ve been unable to stop distilling, taking breaks only because I know I have to.

I once asked Davey how long it would take to learn a language well, since he mentioned it in a video. Good thing he’s an experienced accountant, because maths aren’t my strong point. He showed that each page will take about an hour on average (20 minutes initially, and then less and less for each list), meaning you can simply divide the number of words you want to learn by 25, and you have the number of hours. Davey used the example of 15 000 words, which would take 600 hours of effective time to run through the Goldlist method. If you spent 600 hours on a language in high school, chances are you still wouldn’t have come very far, let alone have a vocabulary of 15 000.

The only thing that could even start to compete with this in terms of efficiency, would probably be electronic flashcards. However, they have the unfortunate downside of boring me to death, so I much prefer the Goldlist, which Davey has fittingly called “the lazy person’s way to learn”. It’s amazing. Last year, I started casually goldlisting some Chinese, and before I knew it, I could chat with Chinese people I met on the metro in Mandarin. And I can always come back and add new words, because I know the old ones are already in my long-term memory. They will never need to be relearned, only reactivated. Because of this, you will always move forward when using the Goldlist Method, never going backwards to check if you still know the words.

And it’s not limited to vocabulary learning either. You can put grammar rules, inflection paradigms, or anything else that can be broken into pieces and remembered. If it can’t be broken into pieces that small, you can simply modify it so you can use it anyway, like Uncle Davey did for remembering Chinese characters.

And the best thing is that it’s completely free for everyone to use. It’s practical, accessible, effective, fun, and easy. What more could you want in your language studies?